Because our lives are so short, our tendency is to think of the universe as stable, unchanging, and eternal. This was codified into our species' most important doctrines for thousands of years, and even Einstein believed in this so fervently that he made the biggest blunder of his career- the

Cosmological Constant, which appeared to be in direct defiance of his own magnum opus- the Theory of Relativity.

These theories of a static universe were exploded over the course of the 20th century, and in its closing years it was discovered that not only is the universe expanding, but accelerating in its expansion- driven by a mysterious force that has not yet been identified and only given the name of

Dark Energy.

The universe, it turns out, is actually a very chaotic, dynamic, and unstable place. It merely

appears stable in our human eyes because the time spans that these changes take place in are so long- but from the point of view of a black hole for instance, they are in fact quite rapid. Such is also the case with biological evolution. As Carl Sagan stated in episode eight of

Cosmos: "from the point of view of a star, life on Earth evolved very rapidly."

So, where did the universe come from and where is it going? The influential book

The Five Ages of the Universe by Fred Adams and Gregory P Laughlin goes over the question in detail. Unfortunately, an admirer of the beauty of the cosmos will not like what it is in store for. The ugly truth is that the

2nd Law of Thermodynamics essentially signs the universe's death warrant. Chaos must increase over time. Order turns to disorder, and energy in the universe must decrease.

The road map of the cosmos is marked below:

1st Age: The Primordial Era

This age began with the Big Bang and lasted until the first stars began to form. It is believed that the inflation of the universe began immediately after the Big Bang, instantly expanding it exponentially in size. The earliest thing we can see- the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, which took place around 380,000 years after the Big Bang, is a product of this period. The universe became transparent and matter, which at this point consisted only of hydrogen, helium, and a tiny amount of lithium, began to coalesce. In the centers of dense clouds of hydrogen, thermonuclear fusion began to take place.

|

| The Cosmic Microwave Background, a remnant of the Primordial Era |

2nd Age: The Stelliferous Era

The thermonuclear reactions at the end of the Primordial Era signified the creation of the first stars, and the blackness of the universe was set aglow with light. The "star bearing" age had begun. As you might expect, this is the era in which we live- the golden age of the universe, awash with light, color, and, we are given reason to expect, life.

The first generation of stars was typically very massive- hot blue stars that burned through their fuel in only a few million or tens of millions of years. Though this sounds like an impossibly long time, from the point of view of a star, it is but a brief instant.

These first generations of stars fused hydrogen into helium, and then helium into carbon and oxygen, and then those into even heavier elements. The short-lived blue giant stars exploded these heavier elements back out into space in spectacular supernovae, creating new stars and systems like our own sun and solar system, and it was through these heavier elements that the building blocks of life, created in the stars, eventually coalesced into life itself. In this era, the remains of dead stars are the building blocks of new ones. Stars are almost literally like phoenixes rising from the ashes.

Eventually however, there will be no hydrogen left to support new stars. Each generation of stars is slightly less massive than its predecessors, and the free clouds will eventually be used up. With no hydrogen left, the existing stars will blink out and not be replaced- starting first with the massive blue stars, and then moving down the line to mid-sized stars like the sun. The universe will be far dimmer, with only faint red dwarves still shining in the latter stages of this era. At this same time, it is also thought that the continuing expansion of the universe will push all galaxies not gravitationally bound to each other so far away that no information, traveling at the speed of light, will ever be exchanged between them again. The only visible things will be objects in each individual galaxy- in whatever form they may take. It is estimated that in about 100 trillion years, the last red dwarves will have finally perished, and the age of stars will be over.

If this sounds depressing to you, be prepared, for the end of the ride is far from here.

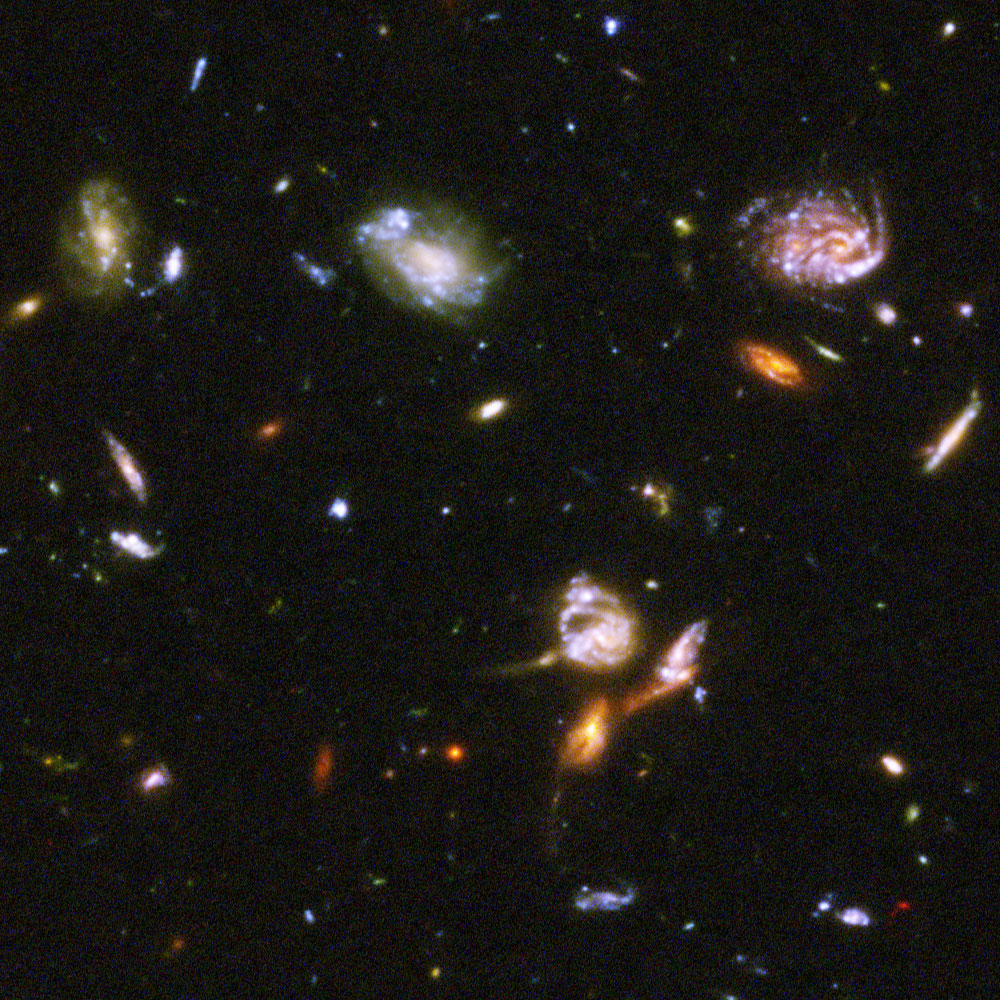

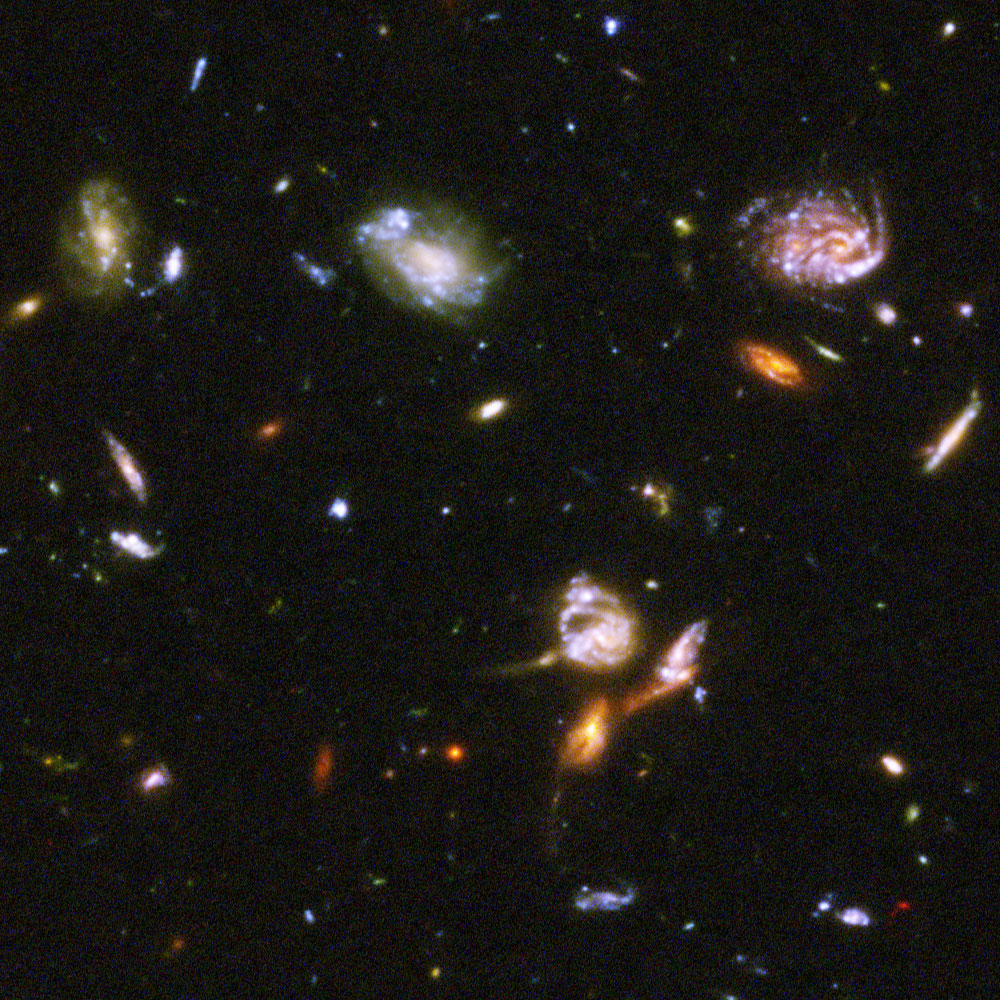

|

| The Hubble Ultra Deep Field. By the end of the Stelliferous Era, all this will be gone. |

3rd Age: The Degenerate Era

This age gets its name from the dominant forms of matter in the universe that will succeed the time of the stars- the various stellar remnants. Brown dwarves (which are stars that never shined), white dwarves, neutron stars, and black holes will be all that remain.

It isn't totally dark in the universe- not yet at least. There is still some radiation coming from the dying stellar remnants, and the occasional supernova may yet happen when collisions amongst white dwarves, for example, occur. But it is a mere shadow of the glories of the Stelliferous Era. The degenerate matter will continue to cool until it no longer shines and eventually, gravitational interactions will scatter the remnants into the aforementioned collisions, outside of the galaxy, or into black holes.

By the end of this era, in 10^40 years, only black holes are still left.

It is hypothesized by some that protons will decay in the Degenerate Era, which will dissolve matter as we know it and thus shorten the time span involved. It is not yet clear whether or not this will be the case, but whatever that case may be, the coming age makes even this one look good.

|

| White dwarves colliding. In the Degenerate Era, stellar remnants like these are the dominant forms of matter. |

4th Age: The Black Hole Era

Welcome to the far, far, far future, where the only objects of note remaining in the universe are black holes. No light is shining and all is dark.

But not forever. Not even black holes are exempt from the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics, and they too will evaporate in the form of

Hawking Radiation. As their mass is continually lost, the black holes themselves will begin to emit light. In the last seconds of their lives, they will shine and

explode colossally, lighting up the darkness of the universe for the first time in what can almost justly be called forever.

But this truly is the last hurrah- the last trick in the bag of the universe. Once the last black hole goes in about 10^99 years, there will truly be nothing left to see.

|

| Artist's conception of a black hole. Even these evaporate very slowly. |

5th Age: The Dark Era

Welcome to the true Dark Ages, where no light will shine- forever. All that remains now is a scattered smattering of sub-atomic particles- electrons, photons, and other particulate matter. Some annihilation events may occur when an electron and positron encounter each other (and essentially cancel each other out of existence) but these will make a snail's pace look like the speed of light. The future of this era seems to be all remaining matter either annihilating or moving so far away that it will never interact with each other.

Either way, it is not a bright future, and an immortal observer would look back and wonder at what had been.

Assesment:

Is there any way out of this death trap that the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics seems to be spelling out for the universe? The answer in most circumstances seems to be "no." Some theories of quantum mechanics predict or suggest that it might be possible to start a new universe, but that's a bit beyond my capability at this point.

This model also makes a number of assumptions- chief among them that the expansion of the universe will continue to occur without interruption. All observational data suggests this will be the case, but who is to say what crazy thing might be discovered in the future?

Beyond anything, the postulated fate of the universe makes me more self-reflective and appreciative of the time in which I'm alive. We are the legacy of the universe itself, privileged with experiencing the glories of its golden age. I think it is an insult to the cosmos that created us to not revel in the time that we're here and be productive members of the cosmic order. We should want to live the good life- and in some ways this brings us full circle, back to Aristotle who was so influential in the model of a static, unchanging universe. The ancient philosopher goes into detail about living the Eudaimon or desirable life- and the universe gives us the prerequisite to do that. It didn't always give us that, and it won't always. Scarcity then, makes the Eudaimon life even more desirable. And so, we must value it, treasure it, and put in the work to make it happen.

|

| Aristotle, by Francesco Hayez (1811) |

Five Ages of the Universe Cosmology Stars